A School that Built our Mothers – Kavari Girls School

Kavari Girls School

People

Teachers and students worked together, each knowing their place, each respecting boundaries. Respect was the discipline. Respect was the rule.

- skerah

-

Post Views: 153

- No Comments

For many of us, when we think of schools that shaped Papua New Guinea, our minds often go straight to Sogeri National High School. But this story is about a different place altogether.

For many of us, when we think of schools that shaped Papua New Guinea, our minds often go straight to Sogeri National High School. But this story is about a different place altogether.

An all-girls school.

Kavari Girls School.

Do you remember that scene in Titanic where the old woman is brought aboard the ship after a treasure box is discovered, and the explorers sit quietly as she tells her story—listening in awe?

It felt a little like that when I discovered this photograph.

I sat my Aunty Edith down. Her hands folded neatly in her lap. Her eyes fixed on something only she could see, staring through the photograph and into the past.

Unlike the movie, this was not gold.

Not jewels.

But memory.

Like the old woman in the film who finally sees the ocean again and allows the past to rise gently to the surface, Aunty Edith leaned back and smiled.

“Kavari,” she said softly.

It was 1968 when she first arrived. She was just fifteen. By 1969, she was sixteen—a young girl stepping into a world run entirely by women, guided by respect rather than fear. The Principal at the time was an Australian woman, Mrs Watson. Firm, but fair. Encouraging, never intimidating.

Kavari Girls School sat quietly in its own space, almost protected by its purpose. It was a girls’ school—and in those days, that mattered. The surrounding area was calm and respectful. Girls were respected. There was no noise, no chaos, no fear. Just young women learning how to stand on their own feet.

Admission was not random. Girls were carefully selected after Grade 6—mostly from St Michael’s, Hagara, and nearby village schools. Many came from Motu Koitabu villages along the Papuan coast, and some from as far as Milne Bay.

Her first memory of Kavari wasn’t a classroom.

It was bread.

Freshly baked. Warm. Golden.

In her very first days, the girls learned to bake—real bread, the kind that smelled like home. They sold it to villagers for fifty cents. Aunty Edith remembers carrying a tray of bread, walking through the village, calling out softly. The bread always sold out. People waited for it. For many families, it became their breakfast.

A typical day felt homely. Not institutional.

There were no uniforms, she recalls, just simple, formal dress. Teachers and students worked together, each knowing their place, each respecting boundaries. Respect was the discipline. Respect was the rule.

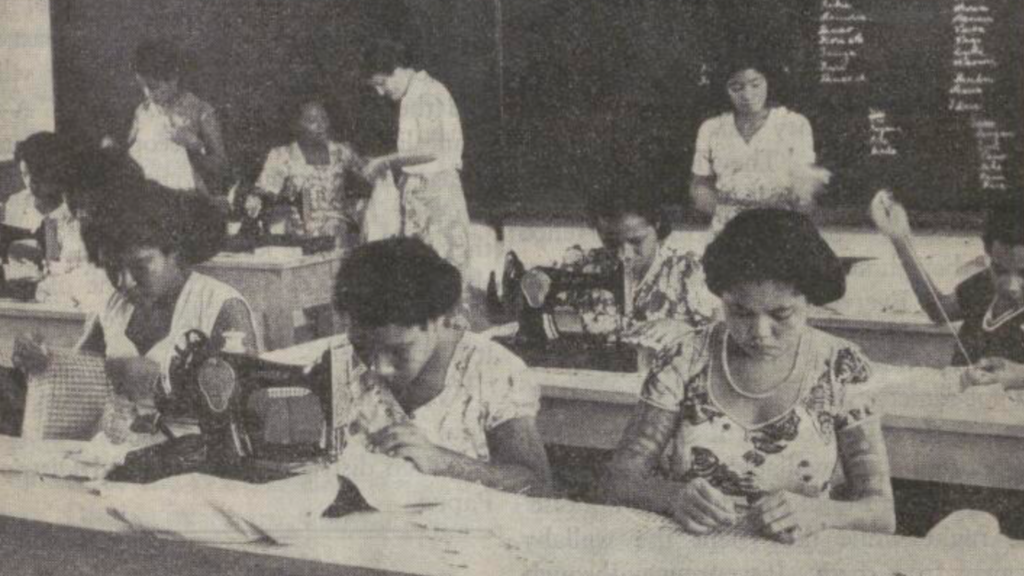

The girls baked together. Sewed together. Cooked together. They even did their own shopping—walking to nearby shops to buy ingredients and materials needed for class. Every girl was involved. Every girl mattered. In today’s language, we would call it inclusivity.

The subjects were practical and purposeful:

Sewing.

Cooking.

Baking.

Typing.

Everything was taught in English.

Typing, in particular, changed her path. She became so skilled that Kavari sent her to work at Harvey Trinder Insurance as a typist. She worked there for eight years—from 1972 to 1979—before leaving for personal reasons. Kavari didn’t just teach skills. It opened doors.

Typing, in particular, changed her path. She became so skilled that Kavari sent her to work at Harvey Trinder Insurance as a typist. She worked there for eight years—from 1972 to 1979—before leaving for personal reasons. Kavari didn’t just teach skills. It opened doors.

But it was the teachers, she says, who shaped the soul of the school.

They weren’t just educators.

They were mothers.

Mrs Vaieke from Hanuabada taught sewing.

Mrs Henao Rarua, also from Hanuabada, taught typing.

And Mrs Solomon from Milne Bay taught cooking.

Mrs Solomon left the deepest impression.

Her bread was famous.

So famous that villagers relied on it. Her students loved her classes so much they would rush to be chosen to sell the bread. The joy wasn’t just in cooking—it was in serving. In being trusted. In seeing people smile because of something you made with your own hands.

(Oh, how I long for this spirit to return—to see once again that simple joy in serving.)

The girls were expected to work hard. To learn. To master household skills, yes—but also to speak. The Principal encouraged public speaking. Girls were taught to stand up, to talk, to lead.

They were being prepared—not just for marriage, not just for work—but for life.

Aunty Edith paused again, her eyes distant.

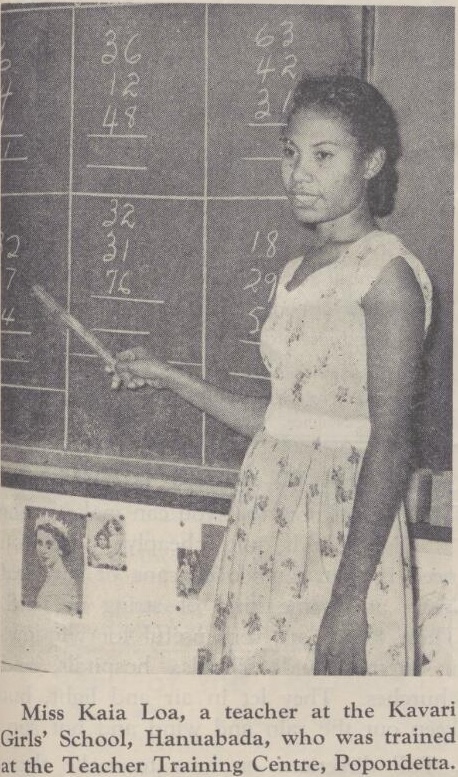

“No,” she said gently when asked about later teachers. “Keke Loa came after my time. She’s much younger. The only teacher from Hanuabada I knew was Henao Rarua.”

Then she smiled—not with nostalgia, but with gratitude.

Kavari was never a romantic love story.

But it was a love story.

A love for discipline without fear.

For womanhood with dignity.

For skills that fed families and built futures.

And as she sat there remembering, one thing became clear:

Some treasures don’t sink.

They live on in the women who carry them forward.

Share & Learn

[email protected]

Request Worksheet

✅ Worksheet will be sent to your email.